|

The prehistory or early life in the Uintas is generally poorly understood, partially because of the area's location near the contact zone between the Great Basin, Colorado Plateau, and Northern Plains cultures. The prehistory of the High Uintas is a meld of these traditions that has resulted in the identification of many enigmatic archaeological sites.

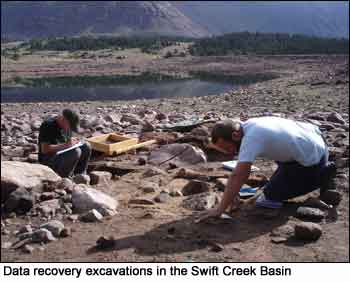

Analysis of artifacts recovered from these sites as part of this study indicates that Native Americans occupied both the Brown Duck and Swift Creek Basins in the High Uinta Mountains as early as 6,000 years ago. For a more complete discussion on Native American use of the High Uinta Mountains click here to download the Data Recovery at Six Prehistoric Sites Report (~4MB).

The study of stone tools and associated artifacts from excavations at sites in Brown Duck and Swift Creek Basins identified stone spear points such as the Pinto Square-shoulder, the Humboldt Concave Base and the Gate Cliff Split Stem at Brown Duck Basin that support the idea that Native Americans used the High Uintas as early as 6,000 years ago. The photos above show (from left to right): a Humboldt-Concave Base Point (5,000-3000 years ago); a Gate Cliff Split Stem (4,950 to 2,250 years ago); and, a Desert-Side notch (no earlier than 700 years ago.)

Stone spear points found in the Swift Creek Basin such as Humboldt Concave Base (5,000 to 3,000 year ago) and Humboldt Series points (5,000 to 3,000), shown respecitvely in the photos to the left, indicate use of the Basin from as early as 5,000 years ago. Stone spear points found in the Swift Creek Basin such as Humboldt Concave Base (5,000 to 3,000 year ago) and Humboldt Series points (5,000 to 3,000), shown respecitvely in the photos to the left, indicate use of the Basin from as early as 5,000 years ago.

Stone materials used to make spear and arrow points and scrapers include various kinds of quartzite, chert, chalcedony and obsidian (volcanic glass). Interestingly, stone tool debris analysis indicates that the obsidian found at these high elevations came from obsidian sources known as Wild Horse Canyon and Pumice Hole Mine in the Mineral Mountain Range in southwestern Utah some 215 miles southwest of the project area. The fact that obsidian from these two sites was obtained from sources at such long distances to the southwest implies that obsidian was either brought up to the mountains from southern Utah or perhaps purchased through exchange or trade (Pomerleau and Weymouth 2009). All obsidian samples recovered were from sites within the Brown Duck Basin and produced hydration dates that also support use of the area between 250 to 900 years ago. Stone materials used to make spear and arrow points and scrapers include various kinds of quartzite, chert, chalcedony and obsidian (volcanic glass). Interestingly, stone tool debris analysis indicates that the obsidian found at these high elevations came from obsidian sources known as Wild Horse Canyon and Pumice Hole Mine in the Mineral Mountain Range in southwestern Utah some 215 miles southwest of the project area. The fact that obsidian from these two sites was obtained from sources at such long distances to the southwest implies that obsidian was either brought up to the mountains from southern Utah or perhaps purchased through exchange or trade (Pomerleau and Weymouth 2009). All obsidian samples recovered were from sites within the Brown Duck Basin and produced hydration dates that also support use of the area between 250 to 900 years ago.

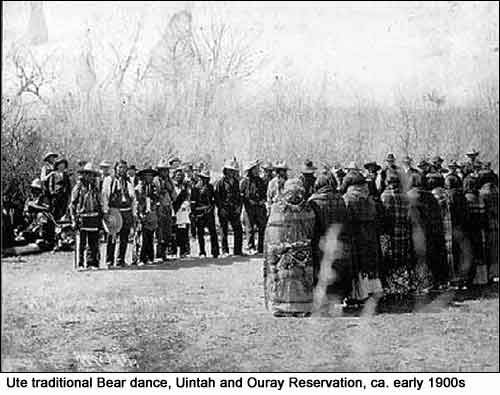

Although evidence exists that Native Americans were present in the high Uintas, it is not clear what they were doing there. Perhaps they were hunting elk, deer, and moose or gathering plants found only at high elevations. According to the Ute, the High Uinta Mountains and its rivers are sacred to the Ute. Here, they gather plants with spiritual and medicinal properties to be used in traditional ceremonies and individual blessings. Ute Tribal Elder, Clifford Duncan, suggests the high Uinta Mountains were a place of healing where Shamans took their sick people to be healed. Although evidence exists that Native Americans were present in the high Uintas, it is not clear what they were doing there. Perhaps they were hunting elk, deer, and moose or gathering plants found only at high elevations. According to the Ute, the High Uinta Mountains and its rivers are sacred to the Ute. Here, they gather plants with spiritual and medicinal properties to be used in traditional ceremonies and individual blessings. Ute Tribal Elder, Clifford Duncan, suggests the high Uinta Mountains were a place of healing where Shamans took their sick people to be healed.

The Uinta Basin was first explored by non-Native Americans over 200 years ago when Spanish Friars Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Silvestre Velez de Escalante made their way through the Uinta Basin in a search for an overland route from Santa Fe, New Mexico to the missions of Monterey, California (Jones and MacKay 1980:66). In the ensuing years, Spanish traders entered the Uinta Basin, establishing a system of trade with the Ute Indians living along this corridor (Morgan 1948).

The second major exploratory campaign into the Uinta Basin occurred in 1825 with the journey of General William Henry Ashley. In April of that year, Ashley followed the Green River southward to Desolation Canyon, 50 miles south of the mouth of the Duchesne River. On his return trip, he retraced his route to the Duchesne River and followed it to where he crossed the Uinta Mountains (Morgan 1964:165, 167). Ashley made copious notes of his experiences and encounters with the Ute Indians in the Basin. It is from these journals that some of the earliest confirmed accounts of Ute living in the area are provided.

In the following years, a number of fur trappers made their way into the area. Some, such as French-Canadian trapper Baptiste Brown, set up trading posts to trade with both the Ute Indians and the travelers along the Spanish Trail (Jones and MacKay 1980:108). In 1833, Christopher “Kit” Carson, who had been trapping in the Basin since the late-1820s, established a trading post at the confluence of the Green and White Rivers. Four years later, in 1837, Antoine Robidoux of Taos, New Mexico erected his own trading post on the west fork of the Uinta River. This trading post, built from adobe, was known variously as Fort Uintah, Fort Wintey, and Fort Robidoux (Jones and MacKay 1980:66). Shortly after Robidoux established his trading post, a second trade center was set up at the future site of Fort Duchesne by a French trapper known only as Du Chasne (Van Cott 1990:143). Little did Du Chasne know the important role this site would play in developing the Uinta Basin.

Early settlement and colonization of the area took place from 1853 to 1861 when Mormon Pioneers made their first scattered attempts to settle the Uinta Basin. It is not clear exactly when the first settlers made their homes in the area. Unlike most areas of Utah at this time, the Uinta Basin was not a primary target of settlement activities for Mormon pioneers. Settlement in the Uinta Basin occurred slowly and was widely dispersed with individual trappers, ranchers, and cattle rustlers constructing isolated homesteads along river valleys. Most of those who did settle in the eastern Utah Territory built their homes in the more hospitable environments of the Ashley Valley, Bridger Basin, and northern Daggett County (Jones and MacKay 1980:109-110).

By 1864, President Lincoln established the Uintah Valley Reserve Indian Reservation (now known as the Uintah and Ouray Reservation). Desires of white settlers to contain Indians on the Uintah Valley Reservation were mitigated by desires of the Ute and other tribes to remain free to pursue their semi-nomadic lifestyles. In 1865, after much negotiation and hardship, Utah Indian Superintendent Oliver Irish and Chief Tabby of the Ute Tribe signed the Treaty of Spanish Fork under which the Ute agreed to move to the Reservation. In exchange, the government agreed to establish farms on the Reservation and pay the Ute annual annuities (Clemmer and Stewart 1986:526). Interestingly, Congress never ratified this treaty. By 1864, President Lincoln established the Uintah Valley Reserve Indian Reservation (now known as the Uintah and Ouray Reservation). Desires of white settlers to contain Indians on the Uintah Valley Reservation were mitigated by desires of the Ute and other tribes to remain free to pursue their semi-nomadic lifestyles. In 1865, after much negotiation and hardship, Utah Indian Superintendent Oliver Irish and Chief Tabby of the Ute Tribe signed the Treaty of Spanish Fork under which the Ute agreed to move to the Reservation. In exchange, the government agreed to establish farms on the Reservation and pay the Ute annual annuities (Clemmer and Stewart 1986:526). Interestingly, Congress never ratified this treaty.

The Reservation was occupied by several bands of Ute Indians on over two million acres of land. Government failure to keep their promises to establish the farms, as well as unrest among the different bands of Ute forced to cohabitate led to a series of uprisings in 1866 known as the Black Hawk War. Many Ute left the Reservation at this time to join Chief Black Hawk in his raids on Mormon settlements in the area. The Black Hawk War continued until 1868 when Chief Black Hawk agreed to cease hostilities and move onto the Uintah Valley Reservation (Jones and MacKay 1980:111). Meanwhile, the federal government continued to pursue the idea of opening the reservation to non-Indians.

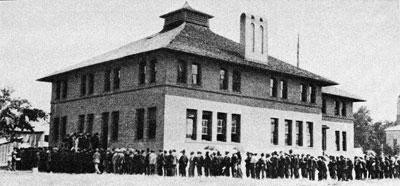

In 1905, a Presidential proclamation was issued opening all un-allotted lands of the Reservation to entry. This action instigated a land rush, in which the Uintah and Ouray Indian Reservation was the last region in Utah to be settled by European Americans. As thousands of non-Indian settlers and would-be miners rushed to the area looking for the best land available for farms and homesteads, a number of towns and communities were established. Among these were the communities of Duchesne, Altonah, Roosevelt, Bennet, Lapoint, and Tridell (Van Cott 1990). The influx of settlers and the establishment of small communities throughout the Basin brought about the need for additional roads and transportation corridors. In 1906, the General Asphaltum Company, which had overseen the construction of the Uintah Railroad, incorporated the Uintah Toll Road Company (Jones and MacKay 1980:92). Under this newly formed company, two separate toll roads were built from Jensen to Vernal and Ouray.

"Men dressed in their Sunday best and women shading themselves with parasols from a warming August sun pressed close to a makeshift stand leaning against one side of the Proctor Academy in Provo, Utah...A large wooden drum stuffed with white envelopes containing the names of prospective homesteaders stood near the front the temporary stand. As the hour drew closer to 9:00 a.m.on August 17, 1905, the crowd of more than a thousand grew increasingly restless. At precisely 9:00 a.m. a signal was given to one of the boys to pull the first

envelope from the wooden drum..." "Men dressed in their Sunday best and women shading themselves with parasols from a warming August sun pressed close to a makeshift stand leaning against one side of the Proctor Academy in Provo, Utah...A large wooden drum stuffed with white envelopes containing the names of prospective homesteaders stood near the front the temporary stand. As the hour drew closer to 9:00 a.m.on August 17, 1905, the crowd of more than a thousand grew increasingly restless. At precisely 9:00 a.m. a signal was given to one of the boys to pull the first

envelope from the wooden drum..."

(Salt Lake Tribune, 17, 18 August 1905; Fuller et al 1989)

By 1905, over 16,000 people arrived in Provo, Utah to register for the right to enter the Uintah and Ouray Reservation. The photo to the right shows how of over a thousand prospective homesteaders stood in line outside the Proctor Academy waiting to hear their names

called for a stake of land in the newly open Indian Reservation. By 1905, over 16,000 people arrived in Provo, Utah to register for the right to enter the Uintah and Ouray Reservation. The photo to the right shows how of over a thousand prospective homesteaders stood in line outside the Proctor Academy waiting to hear their names

called for a stake of land in the newly open Indian Reservation.

The opening of reservation lands brought about a number of significant changes in the use of the Uinta Basin. Among these changes was the creation of the Ashley National Forest by Executive Order of President Theodore Roosevelt on July 1, 1908. The Ashley was developed out of a section of the larger Uintah National Forest Reserve created in 1897 (U.S. Department of Agriculture [USDA] n.d.). In 1902, Chief Grazing Officer Albert F. Potter of the U. S. Division of Forestry had recommended that lands in the area north and west of the Strawberry Valley be set aside as a forest reserve. Three years later, in 1905, President Roosevelt had allotted 1,010,000 acres of land in that area as an addition to the Uintah National Forest (Jones and MacKay 1980:85). The 1908 Executive Order removed that section of land from the Uintah National Forest and designated it as the Ashley National Forest.

As the number of settlers in the Uinta Basin increased, so did tension and dissatisfaction on the Reservation. White settlers were continually diverting water away from Indian farms to supply their own crops. An attempt was made to allay the ill feelings by establishing the Uintah Irrigation Project in 1906  (Jones and MacKay 1980:118). Under the auspices of the Uintah Indian Irrigation Company, this project included construction of 22 canals to service 80,000 acres of reservation lands. The irrigation company was operated with $600,000 in funds paid to the Ute Tribe as part of their compensation for the accession of their lands for settlement (Stalheim et al 1983). (Jones and MacKay 1980:118). Under the auspices of the Uintah Indian Irrigation Company, this project included construction of 22 canals to service 80,000 acres of reservation lands. The irrigation company was operated with $600,000 in funds paid to the Ute Tribe as part of their compensation for the accession of their lands for settlement (Stalheim et al 1983).

Between 1906 and 1935, the Uintah Indian Irrigation Company was responsible, through the use of mostly Ute laborers, for constructing roughly 162 miles of main canals, 635 miles of laterals, and hundreds of associated structures (Stalheim et al 1983). These circumstances, combined with relentless years of drought and a need for early homesteaders to find the means for storing water during drought years, prompted exploration and development of thirteen glacial lakes on the southern slopes of the High Uinta Mountains. At least thirty-nine irrigation and water control companies, including the Dry Gulch Irrigation Company, were formed for service in Duchesne County between 1894 and 1953 (Richards, Davis, and Griffin 1966:23-26). Most of these companies were incorporated between 1905 and 1920. |