Several prominent irrigation companies formed in the Uinta Basin during this period of growth.

Ultimately, these companies developed into corporations or cooperatives that traded stocks for labor, including the Dry Gulch Irrigation

Company (Dry Gulch) and the Farnsworth Canal and Reservoir Company (Farnsworth). Smaller companies in the region included the Farmers

Irrigation Company, Swift Creek Reservoir Company, and Lake Fork Irrigation Company. The sole purpose of these companies was to develop

and distribute irrigation water. A few companies that played central

roles in the historic development of early irrigation systems are still in operation today. Several prominent irrigation companies formed in the Uinta Basin during this period of growth.

Ultimately, these companies developed into corporations or cooperatives that traded stocks for labor, including the Dry Gulch Irrigation

Company (Dry Gulch) and the Farnsworth Canal and Reservoir Company (Farnsworth). Smaller companies in the region included the Farmers

Irrigation Company, Swift Creek Reservoir Company, and Lake Fork Irrigation Company. The sole purpose of these companies was to develop

and distribute irrigation water. A few companies that played central

roles in the historic development of early irrigation systems are still in operation today.

Irrigation Development: Lake Fork Watershed

In 1905, Dry Gulch was granted rights to store water in several remote Uinta Mountain lakes in the

Brown Duck Basin of the Lake Fork Watershed (Fraser et al. 1989:62). Among these was Clements Lake, a large glacial lake at the

northern end of Brown Duck Basin. Although Dry Gulch was granted first rights to storage within the Watershed, it

was not until more than a decade later that Dry Gulch began to actually develop its claims. In 1915, Farnsworth began to express

interest in the area, initiating the first wave of development on Lake Fork Watershed.

Farnsworth, incorporated in 1908, is one of the oldest irrigation companies in the Uinta Basin (Fraser et al. 1989:62).

Following the lead of the larger Dry Gulch, Farnsworth petitioned the Utah State Engineer’s Office for irrigation water storage

rights on the Lake Fork Watershed in 1915 (Fraser et al. 1989:62, 63). The company proposed building dams at Brown Duck, Kidney,

and Island Lakes. By April 1916, Farnsworth was granted rights to store 324, 435, and 851.2 acre-feet of water at the three lakes with the

understanding that all construction be completed by November 1, 1918 (Fraser et al. 1989:62). Farnsworth, incorporated in 1908, is one of the oldest irrigation companies in the Uinta Basin (Fraser et al. 1989:62).

Following the lead of the larger Dry Gulch, Farnsworth petitioned the Utah State Engineer’s Office for irrigation water storage

rights on the Lake Fork Watershed in 1915 (Fraser et al. 1989:62, 63). The company proposed building dams at Brown Duck, Kidney,

and Island Lakes. By April 1916, Farnsworth was granted rights to store 324, 435, and 851.2 acre-feet of water at the three lakes with the

understanding that all construction be completed by November 1, 1918 (Fraser et al. 1989:62).

In 1916, the Farnsworth crew

began horse packing construction supplies up freshly blazed trails to the three lakes (Fraser et al. 1989:65). Actual construction

was initiated in 1917 (Fraser et al. 1989:66, 68). Upon demonstrating that Kidney Lake could provide more water than anticipated,

Farnsworth resubmitted the proposal in January 1917 requesting an additional 1,500 acre-feet of storage. The following year,

Farnsworth re-filed for an additional 1,700 acre-feet of water, pleading for an extension past the November 1, 1918 deadline

(Fraser et al. 1989:63). By November 1919, small earthen dams were in place at the outlets of Brown Duck, Kidney, and Island Lakes.

Farnsworth’s claim on Lake Fork had potential to infringe upon Dry Gulch’s claim at Clements Lake. Dry Gulch initiated efforts to prove its claim in 1919. The proposed Clements Lake Dam would have a storage capacity of nearly 650 acre-feet at maximum capacity (Fraser et al. 1989:72). The United States Forest Service granted Dry Gulch a special use permit to develop the dam in 1921, which authorized Dry Gulch to utilize up to 81 acres of Clements Lake surface (Fraser et al. 1989:71).

To prove their claim, Dry Gulch built a small log dam across the natural outlet on the east end of Clements Lake (Fraser et al. 1989:71, 72). The small dam proved sufficient only to secure Dry Gulch’s interests in the drainage. A larger, formal dam would have to be built in order to utilize Clements Lake to its fullest storage potential.

Dry Gulch contracted engineer Louis Galloway in 1926 to survey the proposed Clements Dam location and plan a pack trail from the Moon Lake trailhead to the dam site (Fraser et al. 1989:71). Galloway’s assistant, Pete Wall, received the contract to construct the dam. Like the Farnsworth crews, prior to snowfall, Pete Wall used packhorses to bring equipment and supplies to the lake. After snow-pack was established, sleds were the preferred method of transporting goods and equipment over such difficult terrain (Fraser et al. 1989:67, 71). Dry Gulch contracted engineer Louis Galloway in 1926 to survey the proposed Clements Dam location and plan a pack trail from the Moon Lake trailhead to the dam site (Fraser et al. 1989:71). Galloway’s assistant, Pete Wall, received the contract to construct the dam. Like the Farnsworth crews, prior to snowfall, Pete Wall used packhorses to bring equipment and supplies to the lake. After snow-pack was established, sleds were the preferred method of transporting goods and equipment over such difficult terrain (Fraser et al. 1989:67, 71).

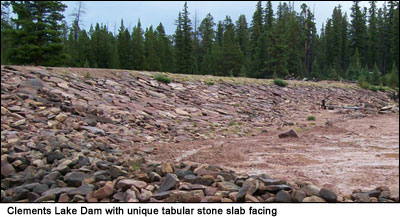

The Clements Lake Dam built by Dry Gulch is very similar to those built by Farnsworth at Brown Duck, Kidney, and Island Lakes. Dry Gulch followed the same strategy for blasting, excavation, foundation placement, and gathering of barrow materials. As a result, the Clements Lake Dam appears very similar in form to the other clay core, earth and stone dams of the region; however, improvements made to the Farnsworth design include the patterned placement of tabular stone facing as armor to the upstream face of the dam, and construction of an overflow spillway, which directed overflow well away from the main dam structure.

The Farnsworth dams were completed at the tail end of a two-year drought that threatened losses on over 50,000 acres of agricultural fields (Fraser et al. 1989:62). Although the dams helped meet irrigation needs of the region, the capacity of the Lake Fork Watershed was viewed as insufficient for the growing number of acres cultivated in the valleys below. The call for more water was met by further water storage projects along adjacent drainage systems. Nevertheless, Farnsworth’s achievements were pioneering efforts in irrigation development in Northeastern Utah.

Irrigation Development: Yellowstone Watershed

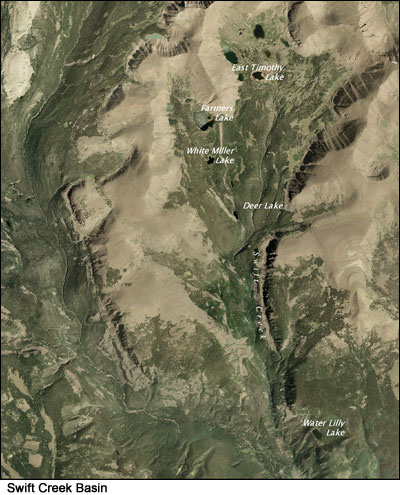

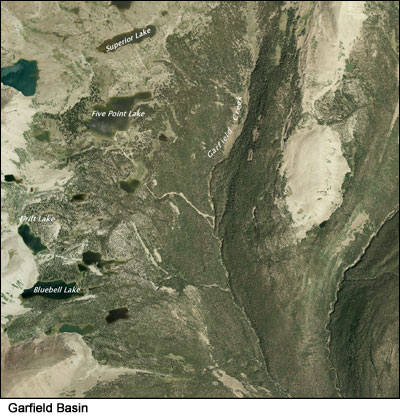

Farmers Irrigation Company (Farmers) was a small company, primarily concerned with providing irrigation to a relatively

minor amount of Uinta Basin farm acreage (Fraser, Jurale, and Righter 1989:76-77). During the 1910s and 20s, the company

petitioned the Utah State Engineer’s Office for irrigation water storage rights to natural lakes in the Yellowstone

Watershed of the Uinta Mountains. Farmers proposed building dams to increase water storage on the Swift Creek Drainage in

Water Lily, Deer, Farmers, and White Miller Lakes, and in the Garfield Basin in Bluebell, Drift, Five Point, and Superior Lakes. Farmers Irrigation Company (Farmers) was a small company, primarily concerned with providing irrigation to a relatively

minor amount of Uinta Basin farm acreage (Fraser, Jurale, and Righter 1989:76-77). During the 1910s and 20s, the company

petitioned the Utah State Engineer’s Office for irrigation water storage rights to natural lakes in the Yellowstone

Watershed of the Uinta Mountains. Farmers proposed building dams to increase water storage on the Swift Creek Drainage in

Water Lily, Deer, Farmers, and White Miller Lakes, and in the Garfield Basin in Bluebell, Drift, Five Point, and Superior Lakes.

By April 1918, Farmers was granted rights to store 723 acre-feet of water at Water Lily Lake, its first reservoir

(Fraser, Jurale, and Righter 1989:77). Permits were granted for 803 acre-feet at Farmers Lake in 1919,

249 acre-feet at Deer Lake in 1925, and 77 acre-feet at White Miller Lake in 1926. Farmers was granted permits for

258 acre-feet of storage at Bluebell Lake and 197 acre-feet at Drift Lake in 1926. In 1927, it obtained permits

for 607 acre-feet of storage at Five Point Lake and 359 acre-feet at Superior Lake (Fraser, Jurale, and Righter 1989:76-80).

A small earthen dam was in place at the outlet of Water Lily Lake and a tunnel had been blasted at Farmers Lake by 1920.

The Farmers Lake Tunnel provided for the release of naturally stored water into White Miller Lake. Work at Water Lily and

Farmers Lakes was quickly followed by construction of dams at Deer Lake in 1925, White Miller Lake in 1926, Drift Lake in 1928,

Five Point Lake in 1929, and Bluebell and Superior Lakes in 1930 (Fraser, Jurale, and Righter 1989:77-80). A small earthen dam was in place at the outlet of Water Lily Lake and a tunnel had been blasted at Farmers Lake by 1920.

The Farmers Lake Tunnel provided for the release of naturally stored water into White Miller Lake. Work at Water Lily and

Farmers Lakes was quickly followed by construction of dams at Deer Lake in 1925, White Miller Lake in 1926, Drift Lake in 1928,

Five Point Lake in 1929, and Bluebell and Superior Lakes in 1930 (Fraser, Jurale, and Righter 1989:77-80).

The dams constructed by Farmers Irrigation Company were small-scale in comparison to the high mountain dams built by

larger irrigation companies, such as Dry Gulch and Farnsworth. Their contribution was never the less significant.

Farmers Irrigation Company ceased operation as an individual entity when it was incorporated into the Moon Lake Water Users Association. (Fraser, Jurale, and Righter 1989:86-87, 90).

Moon Lake Water Users Association

Water problems arose in the 1930s when scarcity of stream flow in April and May, coupled with a short high-water season in the weeks to follow created a critically inadequate irrigation supply. Irrigation companies felt a solution lay in construction of another storage facility. Moon Lake, on the Lake Fork River, was chosen as the site for the reservoir. To raise capital for the Moon Lake Project, interested irrigation companies organized to form the Moon Lake Water Users Association in 1934. It incorporated eight different irrigation companies, including Farnsworth, Dry Gulch, Farmers, Lake Fork and Swift Creek. Each company subscribed to the Association for shares comparable to the number of acre-feet required for its use.

As plans for the future Moon Lake Reservoir were taking shape, stockholders were concerned with regard to over 50 separate water rights with separate allotment priorities flowing into the proposed Moon Lake Reservoir. Stockholders felt it necessary for only one entity to oversee these water rights. As a result, by 1938 all members pooled their natural flow and storage filings and turned these over to the Moon Lake Water Users Association in exchange for their equal allotment on the Lake Fork and Yellowstone Watersheds. As plans for the future Moon Lake Reservoir were taking shape, stockholders were concerned with regard to over 50 separate water rights with separate allotment priorities flowing into the proposed Moon Lake Reservoir. Stockholders felt it necessary for only one entity to oversee these water rights. As a result, by 1938 all members pooled their natural flow and storage filings and turned these over to the Moon Lake Water Users Association in exchange for their equal allotment on the Lake Fork and Yellowstone Watersheds.

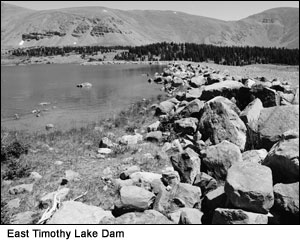

In 1950, the Association obtained a special use permit to construct a dam on East Timothy Lake in the Swift Creek Basin. Uinta Basin farmer Brigham Timothy had increased the lake's storage capacity some time before1920 by building a 12- by 18-foot dam across the lake's natural outlet. The structure consisted of stacked blocks of sod with a wood outlet gate (Fraser, Jurale, and Righter 1989:69). Timothy's water rights were transferred to the Swift Creek Reservoir Company, prior to its integration with Moon Lake Water Users.

In 2006, the Moon Lake Water Users Association began to transfer water storage rights

downstream for storage in the enlarged Big Sand Wash Reservoir, built as part of the Uinta Basin Replacement Project. The Uinta

Basin Replacement Project (UBRP) is a component of the Central Utah Project. [click here, or on the link at the top, for more information about UBRP]

See: Fraser, Clayton B., James A. Jurale, with Robert W. Righter, Beyond the Wasatch: The History of Irrigation in the Uinta Basin and Upper Provo River Area of Utah, edited by Gregory D. Kendrick (1989).

|