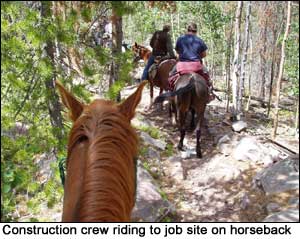

Stabilizing these lakes was a particular challenge due to their remote locations. Specialists determined that for some lakes, the only safe way to complete stabilization in one season required use of mechanized and motorized equipment. Hence, to protect the surrounding wilderness, special approval was obtained from the U.S. Forest Service and equipment and materials were air lifted to the work sites via helicopter. Crews reached the sites by foot and horseback. Stabilizing these lakes was a particular challenge due to their remote locations. Specialists determined that for some lakes, the only safe way to complete stabilization in one season required use of mechanized and motorized equipment. Hence, to protect the surrounding wilderness, special approval was obtained from the U.S. Forest Service and equipment and materials were air lifted to the work sites via helicopter. Crews reached the sites by foot and horseback.

Generally, the stabilization process required removing stop logs, which were in place to reduce erosion and help maintain stability of the dams, and stone rip-rap facing that lined the outlet and upstream potions of each dam. A broad, v-shaped notch was then cut into each dam creating a channel at or near the lakes’ natural level. In this way, lakes could return to their natural hydrologic flow. Rip rap was then replaced along the breach and upstream portion of the new channel. Old headgates were removed and outlet pipes either removed or plugged; however, parts of each historic dam were left in place to preserve them as part of the local heritage. Generally, the stabilization process required removing stop logs, which were in place to reduce erosion and help maintain stability of the dams, and stone rip-rap facing that lined the outlet and upstream potions of each dam. A broad, v-shaped notch was then cut into each dam creating a channel at or near the lakes’ natural level. In this way, lakes could return to their natural hydrologic flow. Rip rap was then replaced along the breach and upstream portion of the new channel. Old headgates were removed and outlet pipes either removed or plugged; however, parts of each historic dam were left in place to preserve them as part of the local heritage.

Follow the links below (also in the menu above) for details on the stabilization process at each reservoir:

Stabilizing the Lake Fork Watershed

Brown Duck Basin

Clements Lake

Island Lake

Kidney Lake

Brown Duck Lake

Stabilizing the Yellowstone Watershed

Garfield Basin

Superior Lake

Five Point Lake

Drift Lake

Bluebell Lake

Swift Creek Basin

East Timothy Lake

Farmers Lake

White Miller Lake

Deer Lake

Water Lily Lake

|